ENSLAVED COMMUNITY

Beginning in October, 2012

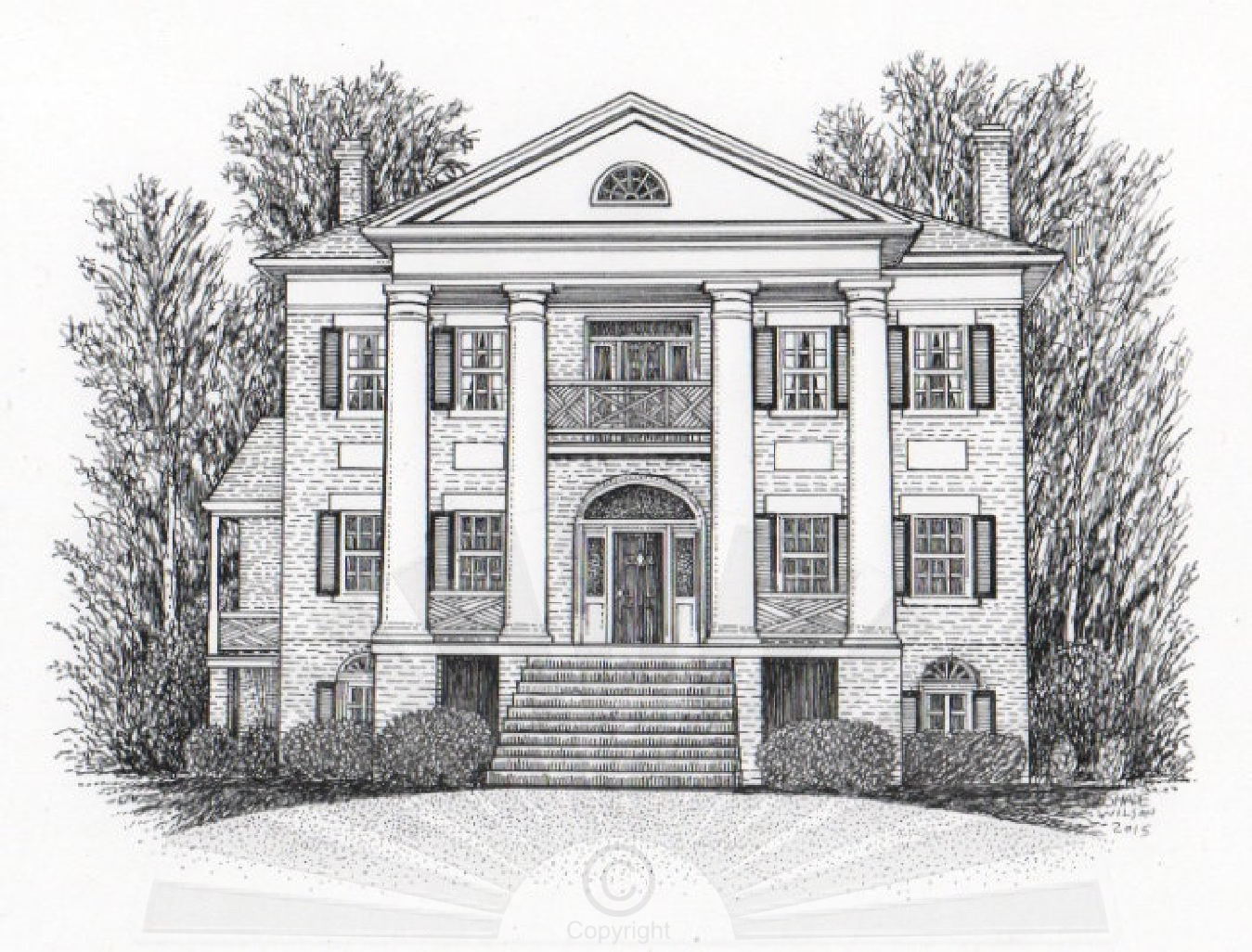

Montgomery Hall, like most other Pre-Civil War plantation estates in Virginia, was run by the labor of enslaved African-Americans. Sadly, these individuals were referred to most often by first name only in wills, inventories, deeds, and tax records. They do not appear at all in census records by name until 1870, making genealogical research prior to 1870 often impossible for their descendants.

The Peyton family records include many last names and details of familial relationships of enslaved people at John Howe Peyton’s Montgomery Hall and his properties in Alleghany County, Virginia. Many of these individuals are mentioned in family letters and some lived out their lives with Peyton family members. No evidence has been found suggesting the manumission of any enslaved people during John Howe Peyton’s lifetime, by his will, or after the death of his wife, Ann Montgomery Lewis Peyton.

Some of the enslaved people at John Howe Peyton’s Montgomery Hall were hired out to work for others for varying periods of time. Peyton engaged in this practice, then prevalent in Virginia and other slave states, as early as 1830 and likely before that time. This practice was continued after his death in 1847. The amount paid to John Howe Peyton and later to his estate by those hiring enslaved men and women was between thirty and forty-five cents per person per day, with an average of forty cents per person per day.

In October, 2012, this database began with a list of names of all known enslaved African-Americans associated with John Howe Peyton and Montgomery Hall and will eventually include all known details of their lives. The first details were added March 5, 2013. Prior to this author’s research, any history of slavery at Montgomery Hall was both unmentioned and unstudied.

A dollar value placed by the name of a human being is a painful thing to see. After careful consideration, the dollar amounts of each individual’s appraisement and sale will be included here. These values often offer clues about an enslaved person’s health, age, and gender, and can sometimes indicate that an individual had special skills or training. This information can be important when no other details of a person’s life are known.

By John Howe Peyton’s will, the Upper Farm in Alleghany County was devised to his son, Yelverton Howe Peyton, a minor. The Lower Farm, also in Alleghany County, was devised to his son, John Lewis Peyton. Howe Peyton and John Lewis Peyton inherited jointly other property in Alleghany County. John Howe Peyton’s widow and children remained at Montgomery Hall. The location given on each page of the database reflects where an enslaved person lived.

There were enslaved African-Americans living at Montgomery Hall during William J. Shumate’s ownership of the property prior to and during the Civil War. All known individuals and any details of their lives were first added in March, 2013. Additional information will eventually be added the Enslaved Community Database and will be included in John Howe Peyton’s Montgomery Hall in 2019.

The Following list of the enslaved African Americans of John Howe Peyton is a work in progress. They lived on his properties in Staunton, Virginia and the Virginia counties of Alleghany, Augusta, and Bath. (Alleghany County was created in 1822 from parts of the counties of Bath, Monroe, and Botetourt. Some of the first tracts of the Alleghany Farm acquired by John Howe Peyton were originally located in Bath County, Virginia.) Names were recorded over time in multiple records by many different people, resulting in variations in the spelling of names. Additional names will be added. There were other enslaved people whose identities are presently unknown and others whose identities have not yet been confirmed.

- Ben Potter

- George Rideout

- Henry Rideout

- Bob

- Lewis Potter

- Scipio

- Cyrus

- Sally Smith

- Jenny Phipps

- Gilbert

- Betty Potter

- Mary “Molly” Susan Potter

- Jane/Jenny Ross

- Julia

- Smith Thomas

- Nancy Lucket

- Fanny, daughter of Nancy Lucket

- Charles, son of Nancy Lucket

- John, son of Nancy Lucket

- Infant girl of Nancy Lucket (Nancy Lucket had 4 children: Eliza, Georgeanna, Charles, and John. Fanny was a nickname for one of the girls.)

- Andrew/Andy Primus

- Margaret Thomas Trimble

- Susan Thomas

- Reuben

- Jane Moore

- Sarah Moore

- Harrietta, daughter of Sarah Moore

- Alice Moore

- Aggy Moore

- Nancy Moore

- Patsy

- Ned Phipps

- Hannah Phipps

- Sam

- Jim

- Eliza

- Jerry, son of Eliza

- Adeline, daughter of Eliza

- Charles (also called Charles Henry), son of Eliza

- Eliza S., daughter of Eliza

- Mary E., daughter of Eliza

- Jane and her children

- Serena and her children

- Ellen

- Old Andy

- Nelly

- Sinah Temperance

- William “Bill” Moore

- Aaron

- Andrew

- Alexander

- Madison

- Bill Cole

- Richard

- Tom Cole

- Ben Cole

- Ben Potter, Jr.

- Prescot Moore

- Jinney/Jinny

- Jane

- Rachael

- Charlotte

- Margaret, daughter of Charlotte

- Page

- Mat Brown

- Patsy

- Maria

- Hannah, infant daughter of Maria

- Caroline

- Jane Scott, daughter of Lucy

- Rachael

- Sam, son of Jane Scott

- Georgianna, daughter of Rachael

- Almira

- Child of Almira

- Margaret, daughter of Thornton

- Eliza, daughter of Lucy

- Charles, son of Eliza

- Lucy, wife of Ruben

- Ruben

- Harriet

- Andy

- Isaac

- Abraham Wallace

- Madison

- Elissa

- Infant of Elissa

- Emily, daughter of Elissa

- Ailes/Ailse/Ailsie

- Francis

- Marshall

- Henrietta

- Tom

- John

- Richard, son of Aggy

- Aggy

- Letitia, daughter of Aggy

- Malvina

- Elvira

- Clara

- Jesse

- Benjamin

- Shedrack

The following list of all known enslaved African-Americans of William Madison Peyton is included because some men were purchased from the estate of his father, John Howe Peyton, in November, 1847, other enslaved men, women, and children may have been purchased from his father prior to 1847, his father may have purchased enslaved men, women, and children from him, and and some are likely related to enslaved families associated with John Howe Peyton. William Madison Peyton also inherited enslaved men and women from his mother’s estate and through his wife’s family. Between the late 1830s and the late 1850s, William Madison Peyton had between 50 and 75 enslaved men, women, and children living at his farms. Peyton sold many enslaved men, women, and children in 1858 when he sold “Elmwood.” William Madison Peyton lived in Staunton, Virginia and the Virginia counties of Bath, Botetourt, Roanoke, and Albemarle. He also owned property in Kentucky and the Virginia counties of Kanawha and Boone (now West Virginia), and lived briefly in New York. William Madison’s farm, “Elmwood” in Roanoke, Virginia later became Elmwood Park. Peyton purchased “Alta Vista” in Albemarle County in 1862.

- William “Bill” Moore

- Aaron/Aron

- Andrew

- Alexander

- Madison

- Bill Cole

Richard (William “Bill” Moore, Aaron/Aron, Andrew, Alexander, Madison, Bill Cole, and Richard are previously listed above under John Howe Peyton.)

- Amelia

- Anderson Family

- Green

- Major

- Lucy

- Nancy

- George Anderson

- Edmond Anderson

- Rosetta Lucas

- Jane Anderson

- Charles Anderson

- Edmond Anderson, Jr.

- Melvin Anderson

- Leslie Anderson

- Eliza Rayford

- Rayford Family

- Betsy Foster

- Peter Jeffries

- Maria Jeffries

- Richard Davis

- Lee Davis

- Miles Robinson

The following is a list of all known enslaved African-Americans of William J. Shumate at Montgomery Hall in Augusta County, Virginia. Shumate also hired out some enslaved individuals to work for others and hired enslaved individuals from other others to work at Montgomery Hall.

- Jesse

- William Henry, son of Mary

- George, son of Mary

- Eliza Ann

- Mary, daughter of Eliza Ann

- Martha

- Son of Martha

- Mary, daughter of Martha

- Nelson

- George Talbot/Taylor

- Archy Gower

- William Ash

- Nancy Ashby

- Sarah Gaskins/Jenkins

- Harriet

- Child of Harriet

- Walker Kelley

- James Hamilton

- Julia A. Johnson

The following list of the enslaved African-Americans of Margaret Cunningham Reed (c. 1747-1827) is included because they are known to have worked and may also have lived at one time on the property later known as Montgomery Hall. In her will Margaret Reed stated: “I have given my negroes except Betty and her children to my friends above named in full confidence that they will treat them with tenderness and humanity. I do hope and trust that they will make the condition of these people whom I have raised as happy as they can be under the laws of our Country.” Margaret Reed also gave a separate memorandum to her executors, Archibald Stuart and William Davis, detailing her wishes for the distribution of her clothing, household items, furniture, and other personal possessions, leaving these items not only to her family and friends, but also to five enslaved women.